|

The

OBV (c.1750 BC), the Sumerian (c.1750 BC) rendition, as well as the SBV

(c.700 BC) Gilgamesh, all share a related version of the subjugation of

Humbaba (alternately, Huwawa) in which one version has it that Humbaba

is subdued, whilst others have it that he is killed. However, one

Sumerian version alone omits Huwawa altogether recounting in place of the

Huwawa tale another tale of a "solitary tree of the Euphrates" which

tells of how this tree came to be occupied by a demon-woman and snakes.

In the SBV Gilgamesh, both the Humbaba tale and another tale of a

tree of rejuvenation at the bottom of a sacred well are told.

The

18th century BC Sumerian: "Bilgames [Gilgamesh] in the Netherworld"

(as translated by George) which tells of the "solitary tree" is of considerable

interest:

"At

that time there was a solitary tree, a willow.... in its base a Snake-that-Knows-no-Charm

had made its nest, in its branches a Thunderbird had hatched its brood,

in its trunk a Demon-Maiden had built her home... Bilgames [Gilgamesh,

brother in this version of the goddess Inanna], took up in his hand [his

bronze axe]. In its base the Snake-that-Knows-no-Charm he smote, in its

branches the Thunderbird gathered up its brood and went into the mountains,

in its trunk the Demon-Maiden abandoned her home and fled to the wastelands.

As for the tree, he tore it out at the roots and snapped off its branches.

The sons of the city who had come with him lopped off its branches..."

lines 114-146, pp.182-183 The Epic of Gilgamesh, by Andrew George

Isbn 0140449191 (Amazon

link)

A

comparison of the Sumerian version of Gilgamesh with the "Standard" Babylonian

version written around 1300 years later is instructive. The oldest SBV

Gilgamesh tablets are those of Assurbanipal's library at Nineveh (George,

introduction, p.xxvii) which thus date it to c.668BC at the

earliest. This version of Gilgamesh was therefore written nearly 100 years

after

Homer's Iliad and Odyssey had been put into writing. The SBV version recounts

what appears to be a different account with vaguely related, but very different

motifs to those that appear in the Sumerian account, all of which are entirely

absent in the OBV Gilgamesh:

"Let

me reveal a closely guarded matter Gilgamesh, And let me tell you the secret

of the gods. There is a plant whose root is like a camel-thorn,... If you

yourself can win that plant, you will find rejuvenation... [Gilgamesh]

tied heavy stones to his feet. They dragged him down into the Apsu, and

he saw the plant. He took the plant himself: it spiked his hands. He cut

the heavy stones from his feet. The sea threw him up on to its shore [with

the plant]... With it a man may win the breath of life.... I shall take

it back to Uruk... At twenty leagues they ate their ration. At thirty leagues

they stopped for the night. Gilgamesh saw a pool whose water was cool,

and went down into the water and washed. A snake smelt the fragrance of

the plant. It came up silently and carried off the plant. As it took it

away, it shed its scaly skin." section vi,

Tablet XI, SBV Gilgamesh c.670-200 BC, pp.118-119 Myths from Mesopotamia

translated by Stephanie Dalley.

In

the SBV Gilgamesh, the significance of the tree, and the snake is recast

and an association is made with the sacred water that the serpent guards,

though the Babylonians never seem to have quite understood an idea that

was clearly alien to their own ideas of the cosmos.

On the "related" Sumerian / OBV

segments:

The subjugation of Humbaba :

Apart from this Sumerian

tale of the destruction of what is remarkably like the Indo-European World-Tree

in the Sumerian "Bilgames in the Netherworld", all subsequent Sumerian,

OBV, and SBV, Gilgamesh versions recount an altogether different tale in

a forest of trees which appears to be irreconcilable with the destruction

of the "solitary tree".

Sumerian

The Sumerian version

of , "Bilgames and Huwawa", "The Lord to the Living One's Mountain"

has it that:

Bilgames (Gilgamesh) and

Enkidu are accompanied by seven companions with mythical abilities, "in

the heavens they shone, on earth they knew the paths... [to the east]",

After crossing seven mountain

ranges, Bilgames "asked no question, he looked no further, Bilgames smote

the cedar... With all the commotion Bilgames disturbed Huwawa in his lair,

he [Huwawa] launched against him his auras of terror." Bilgames deceives

Huwawa who relinquishes one by one his seven auras, "Having used up his

seven auras of terror , he drew near to his lair. Like a snake in the wine

harbour... and making as if to kiss him, [Bilgames] struck him on the cheek

with his fist. Huwawa bared his bright teeth... [Bilgames ties up Huwawa]

Huwawa spoke to Bilgames: 'O deceitful warrior'... The warrior [Huwawa]

sat, racked by sobs he began to weep... 'O Bilgames set me free!' ... Then

the noble Bilgames, his heart took pity on him,... 'O Enkidu, let the captive

bird go off to its place' ... [Enkidu disagrees that Huwawa should be freed

and advises Bilgames so], Huwawa spoke to Enkidu: 'O Enkidu, you use evil

words to him about me'... But as he spoke these words, in rage and fury

Enkidu severed his head at the neck. They put it in a leather bag and took

it before the gods Enlil and Ninlil..." These gods were horrified and returned

the captive auras to the heavens. pp. 152 - 161 George translation

Babylonian

In the OBV

:

"[Gilgamesh and Enkidu pursue

Huwawa who guards the "mantles of radiance" which flee into the forest]...Now

the mantles of radiance are lost in the forest, The mantles of radiance

are lost, the rays have darkened...Enkidu spoke... to Gilgamesh, 'My friend,

catch a bird and where do its fledglings go? Let's look for the mantles

of radiance afterwards. Just as fledgelings, they are flitting about in

the forest! go back: slay him and slay his servant...' Gilgamesh ... tooth

axe... Drew the sword... Gilgamesh slew him at the neck; Enkidu struck

at the heart.... Huwawa the guardian he slew to the ground." OBV

(c.1750BC) Tablet IV p.148, Dalley

Despite obvious differences

in details, these two versions are broadly similar enough to be the same

tale. However, these 2 accounts are so dissimilar to the tale of the solitary

tree, that it appears that different tales have been woven into the fabric

of a "Gilgamesh schematic".

Yet, despite this, it is

evident that in all renditions, including the "solitary willow" which is

"possessed" by the "demon-woman" and which appears in only one Sumerian

version, the Gilgamesh tales share the motif: a central tree.

The tree in the forest

in the related c.1750 BC OBV/Sumerian (Bilgames & Huwawa) tale (irrespective

of species of tree), is guarded by an entity who controls "auras" (or "mantles

of radiance"). In one version they are numbered 7 which means that this

entity guards the "wandering" heavenly bodies (sun, moon & 5 planets

visible to the unaided eye), and so it could be supposed that this is so

for both tales.

The tree in the forest

of trees guarded by Humbaba appears on face value to represent a different

tale to the Sumerian version in which there is no Humbaba guardian and

in which there is instead a solitary tree protected by a serpent,

and a demon-woman with an eagle perched on its summit. In both the instance

of the solitary tree, and the tree in the forest, what Gilgamesh

seeks to achieve is to eliminate a foreign evil. "The first time he [Humbaba]

is referred to is simply this, 'Because of the evil that is in the land,

we will go to the forest and destroy the evil.'" (N.K.Sanders, p. 33 introduction

to The Epic of Gilgamesh. Isbn. 014044100x). As Sanders also notes:

"The forest is ... sometimes the Amanus in north Syria, or perhaps Elam..."

(p. 32). It is not a coincidence that the the tale is set in Syria. At

the time Syria had a large Hurrian component to its population, and the

Hurrian storm god Tessub - who shares features with the gods of the Indo-Europeans

(for instance Zevs and Thor) - was adopted by the (Semitic) Syrians and

was referred to as "Haddad".

It is evident that in their

barest essence both the tale of the solitary tree and the tales

of the tree in the forest are the same. This is the tale of a foreign

interloper. And so it is to sources alien to mesopotamia that a meanig

to the tale might be elucidated: the tales of the Indo-Europeans.

In Greek mythology Athena

is the patron god(dess) of the Greeks. She is the daughter of Zevs. The

symbol of Zevs is. like that of Thor, the eagle parched on the oak. The

powers of Athena lie in her snake-festooned aegis (which according to Hesiod,

is a feature shared by Dios - Zevs). The central motif of the aegis is

the "Gorgoneion", the Medusa-head, the face of terror. In this light, the

demon-woman becomes Athena, the Humbaba monster the guardian gorgoneion.

The tree, with serpent, eagle, demon woman, and "Humbaba" guardian, only

make sense when they are deciphered with a Greek key. Indeed, the SBV Gilgamesh

version makes it incontrovertibly clear that the Babylonians had absolutely

no understanding of what the tale was about which is why both the killing-of-Humbaba

incident and the tree of rejuvenation are told as separate tales.

Above, Athena, with her

sash-like Aegis, with the Gorgoneion.

Athena, is the goddess of

the Greeks. She is attested to in LInear B Tablets which date to the 14th

Century BC, and in Linear A tablets found in Krete. She offers a

model of the "demon-woman" who Gilgamesh expelled. The "Gorgoneion" would

explain the idea of Humbaba.

|

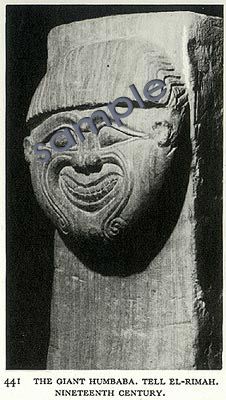

Above, The so-called "Giant

Humbaba" dating to the 19th century BC and found near Nineveh. The image

is from Art of the Ancient Near East

by

Pierre Amiet, Naomi Noble Richard

ISBN:

0810906384

(Amazon

link).

Amiet concedes: "...figures

[which] later enjoyed a particular popularity among the Hurrians...[and]

may indirectly illustrate the presence of this non-Semitic population...

is the giant Humbaba..." p.162

Note the volutes around the

"monster's" mouth. These volutes represent the movement of the sun from

winter to summer solstices. Like much else, they have their origins in

Ireland. However, the later association of the volutes with snakes is Balkan.

Although historians prefer to persevere with the "Abrahamic origin of civilization"

model to explain the transmission of ideas to thus suppose that the Hurrians

were from central Asia, the Hurrians first recorded appearance is on the

Levantine coast. Their final appearance before merging with the Persians

is around Armenia. Their spread is from the coast to the hinterland, moving

from west to east. That they appear on the coast first indicates that they

arrival into the Levant was by sea.

|

|

The

Indo-European context: Greek, Norse, and English tales.

The

Oracle (priestess) at Delphi (whose existence is known to be older than

the SBV Gilgamesh reference to the "tree of rejuvenation"), as one example,

was the Pytho, (which as pointed out earlier is the feminine form of "python").

She represented the forces of Ge (Gaia: earth, whose offspring were serpentine).

The Oracle at Delphi was set at the "omphalos" (navel) of the world. Stretching

from the world-navel to the "chasm", the void around which rotated the

circumpolar stars, was the "trunk" of the "world tree". At the head of

the tree was the eagle, the symbolic bird of Dios "thundering Zevs" (or

"star hurling" -lightning-hurling Dios- as the Greeks referred to

him (which is consistent with the Norse view of the universe with Yggdrasil,

the world tree, at the centre of the universe which was gnawed at its root

by the serpent Nidhogg, with the eagle, bird of the thunder-god Thor at

its summit). Indeed, the Greek word for "sibling" is instructive. The word

used in Greek is "adelphia" (from which "philadelphia" is derived) and

it essentially implies the connection of offspring to the same mother,

as is Delphi, to its source; this is, in essence, the umbilicus, the serpent

which connects Earth's navel to the heavens.

Additionally,

this polar axis was the spring guarded by the serpent, which as Greek myth

recounts was attacked by Kadmus (Cadmus). This very late c. 7th century

BC version of Gilgamesh, and the relationship of the spring, with the tree

of rejuvenation only makes sense when considered in the light of the English

tale of Beowulf, the master over the serpents, especially those serpents

of the water. Beowulf dove into a pool of water for an entire day killing

Grendel who had been decimating the Danish Royalty. The etymology of Grendel

is that he is the grinder. He thus represents the rotational movement of

the heavens which, can be seen as a giant mill in the sky, grinding away

time and therefore life. Thus the pool is the polar void around which the

stars rotate. He symbolises time and death: thus to kill him is to kill

time and thus gain immortality. Immortality thus lies at the bottom of

the cosmic well in both the SBV Gilgamesh and in Beowulf. According to

the "solitary tree" Sumerian version, the holy world tree was possessed

by evil, demons, an affliction in the form of the serpent, the demon maiden,

and thunderbird (eagle). Again, these motifs can only be understood in

the context of Indo-European belief. These "demons" were expunged by Gilgamesh.

The Gilgamesh myth reflects foreign elements which have entered mesopotamia.

It is obvious that they are foreign because their significance appears

not to be understood by the mesopotamian tellers. That Gilgamesh seeks

out to find and destroy this cosmic design which exists in the forests

and mountains that hem in mesopotamia demonstrate their foreigness in the

mesopotamian theatre. This begs the question: when did Indo-Europeans arrive

at mesopotamia?

[return to snake-worship

VENERATION

OF THE SNAKE]

|